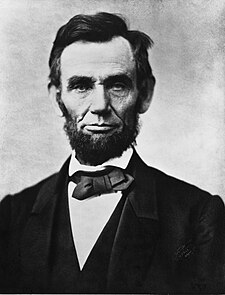

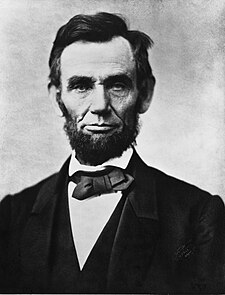

| RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: All over America tonight, parents worry, rightly worry that their children are so easily vulnerable to pornography on the Internet. But in school in the bright light of day, we hand our children history books that describe America as a nation formed by high ideals, yes, but also by perverted emotions-- massacres, Civil War, lynching, assassination. We admit hatred to the American history books. But about the eroticism, about the love that formed us as a people, we barely speak, maybe because we remain Puritans, maybe because the American is so defined by individualism. The sole exception I remember from the American history book, the only love story, was that of Pocahontas; The Indian princess who married an Englishman, had to shoulder the burden for accounting for how we came to be as a people. C.A. Tripp, the sexual researcher and colleague of Alfred Kinsey, has posthumously published a book on Abraham Lincoln wherein he argues that Lincoln was predominantly homosexual. One can just imagine the public reaction. There is no president whose life belongs more to popular myth than Abraham Lincoln. Raymond Massey's Lincoln, log cabin Lincoln who burned the midnight oil, homespun, rough-hewn, honest Abe, the rogue who was also a wit, the wit who was also a sorrowful witness to America's Civil War. ACTOR POTRAYING LINCOLN: What great principle or ideal it is which has kept this union so long together. RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: C.A. Tripp's Lincoln, reluctant to marry, unhappily married, is not inconsistent with the standard biography. But Lincoln as an amorous figure has never been the point of traditional interest. Americans have been inclined to remember Lincoln as a tragic figure-- tall-hatted, brooding, solitary. SINGING: His truth is marching on -- RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: We do not want to hear the ditty Lincoln composed about two queer boys. We do not want to hear about his friendships with young men. C.M. Derekson, Dulmer Elseworth. We do not want to know that Lincoln shared a bed for four years with Joshua Speed, or about their intimate correspondence during their subsequent unhappy marriages. We teach American children to memorize the dates of the Civil War. We teach them perhaps to name Lincoln's assassin. And there is extra credit to the student who can memorize the Gettysburg Address. Because I had a secret to keep as a school boy, I read American history and wondered about the secrets there: The stories of love between cowboys and Indians, slaves and plantation owners, the lonely glances aboard immigrant ships. As a queer man who learned irony, because I could not say directly, who learned the uses of a wider imagination, who learned to read between the lines, where centuries of gay lives lie undetected, I find C.A. Tripp's portrait of a homosexual Abraham Lincoln convincing. Whether or not you agree with Tripp's thesis, what remains remarkable is his audacity, his willingness to speak of homoeroticism within the marbled hallways of American history. Black History Month once more, yet it is still headline news in America when the brown daughter of Strom Thurmond steps out of the shadows to claim a father who was notorious for denouncing race mixing. President's Day, and it is only DNA evidence that tells us what many of our historians were reluctant to tell us. There were brown children behind the great facade at Monticello. Gay activists have argued that Presidents Buchanan and Garfield were probably homosexual. Lincoln is obviously the more provocative case. For one thing, Lincoln is the founder of the political party that is today bent upon denying homosexuals the right to marriage. But I'm not interested in the political implications of Lincoln's intimate life. I am interested that Lincoln, along with Walt Whitman, those two most important voices for national unity at a time when Americans were killing one another, as gray against blue, Lincoln and Whitman may have both been unable to speak of their love. I'm Richard Rodriguez. |

No comments:

Post a Comment