Aloha from Oahu, and especially from the Island of Hawaii, itself...

Aloha from Oahu, and especially from the Island of Hawaii, itself...

First a look back into the future:

Afloat on the peaceful PacificPhoto by Jameson

And now all you ever wondered about the Big Island:

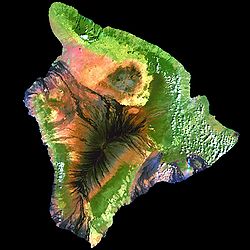

Hawaii (island)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Island of Hawaiʻi (called the Big Island or Hawaiʻi Island) is a volcanic island in the U.S. state of Hawaiʻi in the Pacific Ocean. With an area of 4,028 square miles (10,432 km²), it is the largest island in the United States and larger than all of the other Hawaiian Islands combined.

Hawaiʻi is said to have been named for Hawaiʻiloa, the legendary Polynesian navigator who first discovered it. However, other accounts attribute the name to the legendary land or realm of Hawaiki, a place from which the Polynesians originated (see also Manua), the place where they go in the afterlife, the realm of the gods.

The Island of Hawaiʻi is administered under the County of Hawaiʻi. The county seat is Hilo. It is estimated that as of the year 2003, the island had a resident population of 158,400.

[edit] History

Hawaiʻi was the home island of Kamehameha the Great, who by 1795 had united most of the Hawaiian Islands under his rule after several years of warfare and conquest. He gave his kingdom the name of his native island, which all the islands are now known as, Hawaiʻi. Captain James Cook, who made the Western world aware of these "Sandwich isles", was killed on Hawaiʻi in Kealakekua Bay.

[edit] Geology and geography

The Island of Hawaiʻi is built from five separate shield volcanoes that erupted somewhat sequentially, one overlapping the other. These are (from oldest to youngest):

Interpretation of geological evidence from exposures of old surfaces on the south and west flanks of Mauna Loa led to the proposal that two ancient volcanic shields (named Ninole and Kulani) were all but buried by the younger Mauna Loa.[3] Geologists now consider these "outcrops" to be part of the earlier building of Mauna Loa.

View north from upslope Kohala showing Haleakalā, Maui in the distance

In greatest dimension, the island is 93 miles (150 km) across and has a land area of 4,028.0 square miles (10,432.5 km²),[4] representing 62% of the total land area of the Hawaiian Islands. Measured from its base at the sea floor, to its highest peak, Mauna Kea is the tallest mountain in the world, even taller than Mount Everest, according to the Guinness Book of Records. Traditionally, Hawaiʻi is known as the Big Island because it is the largest of the Hawaiian Islands and some confusion between Hawaiʻi Island and Hawaiʻi State can be avoided.

Because Mauna Loa and Kīlauea are active volcanoes, the island of Hawaiʻi is still growing. Between January 1983 and September 2002, 543 acres (220 ha) of land were added to the island by lava flows from Kīlauea volcano extending the coastline seaward. Several towns have been destroyed by Kīlauea lava flows in modern times: Kapoho (1960), Kalapana (1990), and Kaimū (1990).

Steam plume as Kīlauea red lava enters the ocean at three Waikupanaha and one Ki lava ocean entries. Some surface lava is seen too. The image was taken 04/16/08.

Hawaiʻi is the southernmost island in the Hawaiian archipelago, and contains the southernmost point in the United States, (Ka Lae). The nearest landfall to the south would be in the Line Islands. To the north is the island of Maui, where East Maui Volcano (Haleakalā) is visible across the Alenuihāhā Channel.

18 miles (29 kilometers) off Hawaiʻi Island's southeast coast is the undersea volcano known as Lōʻihi. Lōʻihi is an actively erupting seamount that lies 3,200 feet (975 m) below the surface of the ocean. It is thought that continued volcanic activity from Lōʻihi will cause the volcano to eventually breach sea level and later attach at the surface onto Kīlauea, adding even more land to Hawaiʻi's surface area. This "event" is presently predicted for a date several tens of thousands of years in the future.

Hilina Slump or the Great Crack is an 8-mile (13 km) long, 60 feet (18 m) wide and 60 feet (18 m) deep crack in the island, situated in the district of Kaʻū. The Great Crack is one of many series of cracks and rifts that were formed by eruptions and, in fact, is an extension of the southwest rift zone. Often these rifts are the sites of volcanic eruptions and occasionally a rift can be so deep and so fractured that it can cause a chunk of the island to fall into the ocean.

Some believe that the Great Crack is a result of the south flank of the Big Island moving away from the rest of the island. Speculation abounds that some day, perhaps soon, a major chunk of the island will break away and fall into the ocean, resulting in turn in a huge tsunami and earthquake. This actually does happen every ten thousand years or so, so it is not outside the realm of possibility. Others believe the Great Crack is not a fault that will break the island apart, but instead was created (probably thousands of years ago) as a result of the crust moving apart slightly due to magma forcing itself into the rift zones. The Great Crack has been measured and is tracked and there is no indication that it is enlarging in any way or that the island is shifting near this point. Furthermore, the walls of the crack have been shown to fit together perfectly, thus proving that the crack was a widening of once joined ground.

One can find trails, rock walls, and archaeological sites from as old as the 12th century around the Great Crack. Much of these finds are on the park side of the fence. About 1,951 acres (790 ha) of private land beyond the fence were purchased during the Bill Clinton administration specifically to protect the various artifacts in this area as well as to protect the habitat of the turtles. However, near the end of the crack is an area of land between the fence, the crack and the ocean which is not part of the park land and does have many archaeological artifacts on it.

In 1823 a very fluid flow of lava came out of a 6-mile (10 km) portion of the crack and made its way to the ocean.

On April 2, 1868, an earthquake in this area with a magnitude estimated between 7.25 and 7.75 on the Richter scale rocked the southeast coast of Hawaiʻi. It triggered a landslide on the slopes of Mauna Loa, five miles (8 km) north of Pahala, killing 31 persons. A tsunami claimed 46 additional lives. The villages of Punaluʻu, Nīnole, Kawaʻa, Honuʻapo, and Keauhou Landing were severely damaged. According to one account, the tsunami "rolled in over the tops of the coconut trees, probably 60 feet (18 m) high ... inland a distance of a quarter of a mile in some places, taking out to sea when it returned, houses, men, women, and almost everything movable." This was reported in the 1988 edition of Walter C. Dudley's book, "Tsunami!" (ISBN 0-8248-1125-9).

On November 29, 1975, a 37-mile (60 km) wide section of the Hilina Slump plunged 11 feet (3 m) into the ocean, widening the crack by 26 feet (8 m). This movement caused a 7.2 magnitude earthquake and a 48 feet (10 m) high tsunami. Oceanfront properties were washed off their foundations in Punaluʻu. Two deaths were reported at Halapē, and 19 other persons were injured.

The northeast coast of the Big Island has also suffered tsunami damage from earthquakes that triggered waves from Chile and Alaska. Downtown Hilo was severely damaged in 1946 and 1960, with many lives lost. Laupāhoehoe alone lost 16 school children and 5 teachers in the 1946 tsunami.

[edit] Demographics

As of 2000, there were 148,677 people, 52,985 households, and 36,877 families residing in the county. The population density was 14/km² (37/mi²). There were 62,674 housing units at an average density of 6/km² (16/mi²). The racial makeup of the county was 31.55% White, 0.47% African American, 0.45% Native American, 26.70% Asian, 11.25% Pacific Islander, 1.14% from other races, and 28.44% from two or more races. 9.49% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 52,985 households out of which 32.20% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.60% were married couples living together, 13.20% had a woman whose husband did not live with her, and 30.40% were non-families. 23.10% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.00% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.75 and the average family size was 3.24.

In the county the population was spread out with 26.10% under the age of 18, 8.20% from 18 to 24, 26.20% from 25 to 44, 26.00% from 45 to 64, and 13.50% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females there were 100 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98 males.

[edit] Economy

The big Island from the air

Sugarcane was the backbone of Hawaiʻi Island's economy for more than a century. In the mid-twentieth century, sugar plantations began to downsize and by 1996, the last sugar cane plantation had closed down.

Today, most of Hawaiʻi Island's economy is based on tourism, centered primarily on the leeward (kona) or western coast of the island in the North Kona and South Kohala districts. However, diversified agriculture is a growing sector of the economy of the island. Macadamia nuts, papaya, flowers, tropical and temperate vegetables, and coffee are all important crops. In fact, because of Hawaiʻi Island's reputation for growing beautiful orchids, the island has the nickname "The Orchid Isle." Cattle ranching is also important. The Big Island is home to one of the largest cattle ranches in the United States, Parker Ranch, which is situated on 175,000 acres (708 km²) in and around Kamuela. Astronomy is another industry, with numerous telescopes situated on Mauna Kea owing to the excellent clarity of the atmosphere at its summit and the lack of light pollution.

[edit] Tourist information

The big Island

lava flow from the air

The Big Island is famous for its volcanoes. Kīlauea, the most active, has been erupting almost continuously for more than two decades. At the coast where the lava meets the ocean, one can sometimes see billows of white steam rising from off the shoreline. At night, the lava lights up the steam to give an orange glow. When the molten lava makes contact with the ocean, the sea water turns into steam, and the sudden cooling of the lava causes the newly formed lava rocks to explode and crack into small pieces. The broken up lava is further ground into black sands along the shore by the ocean waves. Black sand beaches are common on the Big Island.

[edit] Places of interest

Lehua blossoms (

ʻōhi

ʻa lehua), Hawai

ʻi

[edit] Cities and towns

Map of Hawaii with cities

[edit] Colleges and universities

[edit] Transportation

Two airports serve Hawaii Island:

[edit] References

[edit] Further reading

- MacDonald, G. A., and A. T. Abbott. 1970. Volcanoes in the Sea. Univ. of Hawaiʻi Press, Honolulu. 441 pages.

[edit] External links

happy trails...

Jack