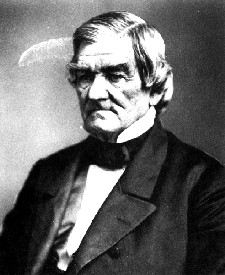

Chief John Ross of the Cherokee Nation

Born on October 3, 1790 at Turkeytown, Alabama

John Ross was the son of Daniel Ross, a Scotsman who had gone to live among the Cherokee during the American Revolution. His mother was also ¾ Scottish and ¼ Cherokee.

John’s father, Daniel, established a store at Chattanooga Creek near the foot of Lookout Mountain, which operated until about 1816. Determined that his children would receive a quality education, Daniel built a small school and hired a teacher. It was here that John Ross received his early education before attending another school in Kingston, Tennessee and later the Maryville, Tennessee Academy.

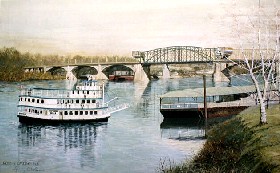

Ross' Landing, painting by Larry Dodson, courtesy

Though only 1/8th Cherokee, Ross was of Indian heritage through and through. Early in his life, he witnessed much brutality on the American frontier as both Indians and settlers alike were constantly raiding the Cherokee villages.

Also an astute businessman, Ross was involved with a number of business ventures, owned a 200 acre farm, and owned a number of slaves.

Over the next ten years, Ross fought the white settlers who were attempting to displace the Cherokee from their lands. Fighting not with weapons, but with words, he turned to the press and the courts to support the Cherokee cause.

When gold was discovered in White County, Georgia in 1828, the state began to push even harder for removal of the Indians. The Georgia legislature soon outlawed the Cherokee government and confiscated tribal lands. When the Cherokee appealed for federal protection, they were rejected by President.

Though winning several court rulings, it would make no difference as Ross’ former comrade, President Andrew Jackson authorized the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

The Jackson Administration began to put pressure on the Cherokees and other tribes to sign treaties of removal but the Cherokees rejected any proposals. However, when Jackson was reelected in 1832, some of the Cherokees believed that removal was inevitable. A Treaty Party, led by Major John Ridge, believed that it was in the best interest of the Cherokee Nation to get the best possible terms from the U.S. government. Cautiously, Ridge began unauthorized talks with the Jackson administration.

However, Chief John Ross and the majority of the Cherokee people remained adamantly opposed to removal. In 1832, Ross cancelled the tribal elections and the Council impeached Ridge, and a member of the Ridge Party was murdered. The "Treaty Party" responded by forming their own council, which represented only a small minority of the Cherokee people. Both the Ross government and the Ridge Party sent independent delegations to Washington.

In the end, 500 of the Cherokees (out of thousands) supported a treaty to cede the Cherokee lands in exchange for $5,700,000 and new lands in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma.) Though the actions was repudiated by more than nine-tenths of the tribe and was not signed by a single elected tribal official, Congress ratified the treaty on May 23, 1836.

Chief Ross and the Cherokee National Council maintained that the document was a fraud and presented a petition with more than 15,000 Cherokee signatures to congress in the spring of 1838. Other white settlers also were outraged by the questionable legality of the treaty. On April 23, 1838, Ralph Waldo Emerson appealed to Jackson's successor, President Martin Van Buren, urging him not to inflict "so vast an outrage upon the Cherokee Nation. But it was not to be.

Soon, the Cherokees were forced to move to Indian Territory on what would become known as the Trail of Tears. Along the 2,200 mile journey, road conditions, illness, cold, and exhaustion took thousands of lives, including Chief John Ross' wife Quatie. Though the federal government officially stated some 424 deaths, an American doctor traveling with one the party estimated that 2,000 people died in the camps and another 2,000 along the trail. Other estimates have been stated that conclude that almost 8,000 of the Cherokee died during the Indian Removal.

Once the tribe was relocated to a site near present day Tahlequah, Oklahoma, John Ross was reelected Principal Chief. Major Ridge was killed the same day for violating the law forbidding unauthorized sale of property. Soon, land was set aside for schools, a newspaper, and a new Cherokee capital.

During the Civil War, the Cherokee aligned themselves with the Confederacy, a declaration that repudiated any treaties that had been formerly signed with the Federal Government.

In September, 1865, Ross attended the Grand Council of Southern Indians at Fort Smith, Arkansas where new treaties between Cherokee and the Federal government were prepared. In July, 1866, though in failing health, he accompanied a delegation to Washington where new the treaties were signed on July 19, 1866. Soon after the treaties were signed, Ross took to his bed at the Medes Hotel in Washington D.C. where he died on August 1, 1866. His body was returned to Indian Territory where he is buried at Ross Cemetery in Park Hill, Oklahoma.

© Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated March, 2008

Chief John Ross, courtesy the Smithsonian Institution

http://www.legendsofamerica.com/NA-JohnRoss.html

No comments:

Post a Comment